I do believe there is such a thing as luck in writing. It happens when . . .

I do believe there is such a thing as luck in writing. It happens when . . .

- A writer’s manuscript hits an agent’s or an editor’s desk just after the agent/editor has had a fantastic lunch, or just won a freebie trip to Paris, or just scored a date with a dreamboat, or is otherwise in a really good mood.

- A writer’s manuscript about XYZ hits an agent’s or an editor’s desk just after the agent/editor has learned, observed, or been informed that books on subject XYZ are so hot they’re melting holes on bookstore shelves.

- An author’s book about XYZ is published just when subject XYZ tops a trend, or achieves peak news interest, or scores the #1 position in Google searches.

- A celebrity reads an author’s book and sheds tears (sorrow or laughter – your pick) talking it up on a top-rated talk show.

- A journalist finds an aspect of the author’s life/book (that will help sell the author’s book if broadcast) fascinating, writes an article about it – and the article is picked up for syndication by Reuters. Or, alternatively, the journalist writes the article for a top tier newspaper (LA Times, New York Times, Washington Post, etc.) – and second and third tier newspapers take note and cascade their versions of the article.

Lucky instances 1 & 2 can help an author place a book with one of the Big Six Publishers. Lucky instances 3, 4 & 5 can make sure the book has “legs” – i.e., that it jumps off bookshelves and into readers’ arms – hopefully nestling close to their hearts.

But here’s the rub – in all of the above instances, one constant needs to be in play: the manuscript/book in question needs to be a top quality work.

Luck has a way of manisfesting itself on preparation.

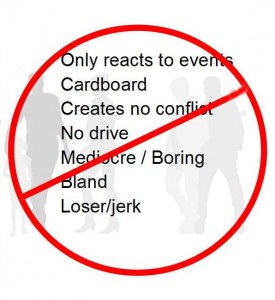

Nonfiction books need to be well-written, researched, presented. Fiction books need to – well, look at some of the blog posts on this site about how to write reader-pleasing fiction.

When quality isn’t in place, an agent or editor will look for other options (or extensive revisions) – even if your subject matter is trending wildly. If your book does happen to get published, and it falls short of certain criteria for quality, it will languish on the bookstore shelves or readers may buy it but not be keen to buy your next offering. And for writers serious about making authorship a career, the goal is not one book sale, it’s loyal readers.

The takeaway for writers? Don’t worry too much about lucky breaks. They happen sooner or later to writers who focus on creating a body of excellent work – one book at a time. It may not be your first book, or your fifth, that brings your work to the attention of that larger audience hungry for just the kind of books you write. But it will happen sooner or later.

A small group of enthusiastic fans equals word of mouth endorsements – the best kind of marketing.

And if your larger audience discovers you when you produce Book Six, guess what happens? That’s right. They go back and buy the other five books you wrote as you built your ouevre.

In short, writers who stick to the basics – writing the best books they can – make their own luck.