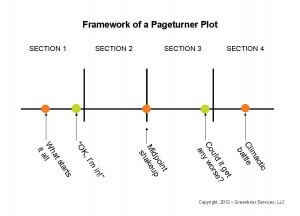

In Section 1 of your Novel (its opening Scenes), you:

- Establish the world of the Novel (show the Hero’s “normal” world).

- Introduce the “What Starts It All” (Hero bumps up against a problem caused by an antagonistic force).

Generally, the Hero does not immediately start struggling against the antagonistic force (trying to resolve the Key Problem he faces). He will usually, in fact, resist taking action, drag his feet, find reasons not to “go for it.”

This delay serves several purposes:

- It allows the reader to learn more about the problem and to absorb its significance.

- It allows the reader to develop empathy for the Hero.

- It mirrors the real world. How many of us welcome trouble with open arms? No. Our natural reaction is often to find a way to avoid clashing with antagonistic forces.

- The Hero’s delay highlights the drama of the moment when he finally makes the decision to enter the fray.

Then, in the final Scene in Section 1 of your Novel, the hero will confront a surprising development that turns his life upside down in some way and forces him to decide, “Okay, I’m in.” His “Okay, I’m In” decision will take him and the reader on a new and unexpected path.

In screenwriting, this is also known as Plot Point 1, or Turning Point One.

The “Okay, I’m In” moment is a direct result of the “What Starts It All” event.

In J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, the “What Starts It All” event occurs when the Hero, Holden Caulfield, gets expelled from his boarding school due to his failing grades. The “Okay, I’m In” moment is when Holden – disgraced and distressed – decides to run away from school and spend a few days on his own in New York City.

The antagonistic forces in Salinger’s novel, are society’s expectations of Holden coupled with the emotional problems he has been experiencing since his younger brother’s death, problems which have left him increasingly incapable of handling his everyday responsibilities. Holden goal in fleeing to New York is to get some R&R, which he hopes will restore his sense of balance and his ability to cope.

Note: Just to complicate things: yes, it is possible to begin a novel with the “Okay, I’m In” Scene. When that happens, the novelist restructures Section 1, filling in the “What Starts It All” and establishing what was the Hero’s normal world in the Scenes that follow the Big Bang opening Scene.

However, there is a real risk in rewiring the Section 1 story this way: place the “Okay, I’m In” Scene first thing, and you may fail to establish the reader’s empathy for your Hero. You want your reader to care about your Hero; it is quite a challenge for a writer to make those careful word choices and Scene set ups that enable a reader to care for a Character he or she hardly knows.

Happy Writing!