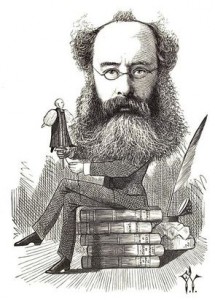

One author writing about Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope – one of the most successful writers of his day – called him a “Novel Machine.”

Trollope’s first novel was published in 1847 while he held a full-time job as a post office civil servant. For the next 20 years, while remaining in his full-time job, he was able to produce at least a book a year and sometimes three. During his lifetime, he penned 47 novels and 16 additional books.

Trollope woke up every day up at 5:30 am and had a cup of coffee. he would then read what he had written previously for half an hour, then he would write for the next two and a half hours. His output was 1000 words per hour. In two and a half hours, he produced – about 10 modern manuscript pages a day. This, Trollope wrote, in his autobiography, “allowed me to produce over ten pages of an ordinary novel volume a day, and if kept up through ten months, would have given as its results three novels of three volumes each in the year.” Today, most of us admire these workmanlike habits. What is fascinating, however, is that when Trollope’s Autobiography was published posthumously, after his death in 1882, his reputation took a nosedive. Why? Because Victorian literary sensibilities were taken aback by an author whose means of producing work were apparently so mechanical. Victorian critics felt true poets and authors produced work in the throes of “inspiration.”

The Victorian sentiment is often subtly promulgated by Hollywood – how many scenes have we seen where a writer writing is clearly rapturously transported by his/her work? Okay, it happens. But waiting for “transport” can be like waiting for Godot.

Stephen King was once asked what was the secret of writing success. His answer: “Bum glue.” (Bum here being the British word for the part of your anatomy that needs to be parked in front of a word processor for a good chunk of time in order to produce a manuscript.) Hmm, why does it not surprise me that Stephen King has been prolific too?